Visit the Cinemas of Wartime Paris with UC Davis Film Scholar’s New Book

In 1980-81, Eric Smoodin was a graduate student in Paris. During the year he spent there, Smoodin writes in his most recent book, “I walked home from classes and always passed a cinema along the rue du Temple that never changed its bill.” The cinema was playing Fritz Lang’s Le Tigre du Bengale. “I still remember the young woman who worked in the ticket booth,” Smoodin writes, “always smoking because she had nothing else to do. Practically no one was buying tickets to see the movie.”

So why, he wondered, was it still playing there? Why did cinemas in some parts of the city change their bill all the time, while others showed the same film for a year or more? As Smoodin, a Professor in the Programs in American Studies and Film Studies, explained at a recent DHI Book Chat event, the questions stemming from these initial ones would interest him on and off for the next 40 years. Eventually, they formed the basis of his book, Paris in the Dark: Going to the Movies in the City of Light, 1930-1950 (Duke University Press, 2020).

Mapping the Cinematic Geography of Paris

Paris in the Dark explores two tumultuous decades of Parisian film culture, showing how movies were tied up with the space of the city and its multifaceted audiences. Using the many film magazines that circulated during the period as his primary archive, Smoodin explains that films moved through neighborhoods, around the country, and beyond the borders of France to create a cinema culture that was uniquely Parisian even as it was wide-ranging and international.

In his conversation with DHI Director Jaimey Fisher, Smoodin discussed how the places where movies were shown were often bound up with class. “The places with the most cinemas tended to be the more working-class districts on the outskirts of Paris, [while] the elite cinemas tended to be on the inside, along like the great avenues [like] the Champs-Élysées,” he said. In his book Smoodin describes how at these many and varied cinemas in the 1930s and 1940s, Parisian audiences could see Hollywood films like Frankenstein or Citizen Kane, avant-garde films screened by one of the city’s cine-clubs, or international films from studios throughout Europe.

In his conversation with DHI Director Jaimey Fisher, Smoodin discussed how the places where movies were shown were often bound up with class. “The places with the most cinemas tended to be the more working-class districts on the outskirts of Paris, [while] the elite cinemas tended to be on the inside, along like the great avenues [like] the Champs-Élysées,” he said. In his book Smoodin describes how at these many and varied cinemas in the 1930s and 1940s, Parisian audiences could see Hollywood films like Frankenstein or Citizen Kane, avant-garde films screened by one of the city’s cine-clubs, or international films from studios throughout Europe.

The book also investigates French cinema’s trajectories along colonial routes: in Algiers, for example, audiences experienced a unique hybrid of French and local cinema cultures. As Smoodin explained in his talk, the combination of neighborhood-based film distribution and colonial cinema culture complicates the idea of a French national cinema. This geography of French cinema created fragmented audiences, Smoodin went on, so that “the nation becomes a very complicated space that is both bigger than we thought and also much, much smaller.”

Spaces of Fascism and Resistance

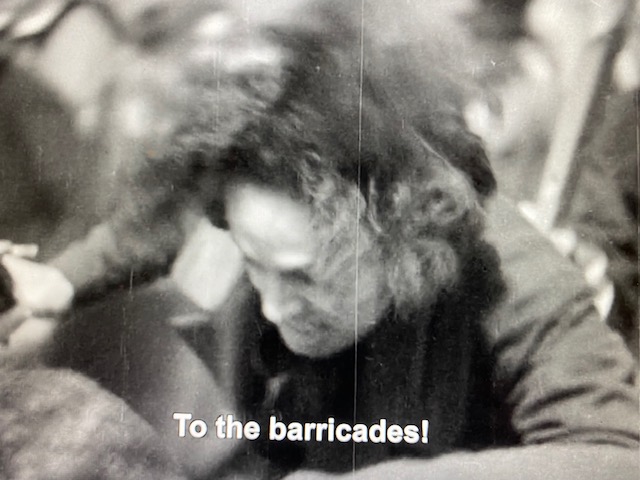

In addition to situating French film within this complex cultural and geopolitical network, Smoodin’s book explores how Parisian cinemas were important to activities not directly connected with the film industry. In the 1930s some cinemas were fascist spaces that were the sites of violent confrontations.

Later, after the Nazis began occupying the city in 1941, “some of the most vexed moments of resistance in Paris...were mini-riots at the projection of German newsreels,” Smoodin said. He explained that even as they used their control of cinemas and film journalism to make life in occupied Paris appear as normal as possible, the Germans also spied on French cinemagoers and disseminated German propaganda through film.

Paris in the Dark discusses the postwar liberation period as well, arguing that the return of French stars who had spent the war in Hollywood ushered in a new era of progressive intellectualism.

The Paris Cinema Project

“The archive is always mundane,” Smoodin said of the primary materials he studied. “At the same time, it’s always inflected by who’s in charge and what’s happening in Paris. You can read various political events through the everyday materials.” Smoodin’s research was made possible by the digital holdings of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, which allowed him to access a huge collection of film magazines from his own study. Not having to travel to Paris for research was both “the best thing about the project and the worst thing,” Smoodin laughed.

Because he found much more in his research than could be included in the book, Smoodin started the Paris Cinema Project, a blog where he posts short entries that build on and extend the book’s arguments. His ongoing work will continue to focus on French colonial spaces like Algiers, “trying to understand what French cinema means in spaces that are French by force of military takeover.”

Paris in the Dark is freely available in an open access edition - read it here.

---

This event was part of the DHI’s Book Chat series, which celebrates the artistic and intellectual ventures of UC Davis faculty in the humanities and allows them to share their new publications, performances, or recordings with the community. Mark your calendars for our Winter and Spring virtual events:

- Julie Sze on Environmental Justice in a Moment of Danger, February 10, 2021, 5:10-6:00pm

- Lorena Oropeza on The King of Adobe: Reies López Tijerina, Lost Prophet of the Chicano Movement, May 26, 2021, 5:10-6:00pm