Dr. Lorena Oropeza Reveals New Facets of Chicano Leader, Reies López Tijerina

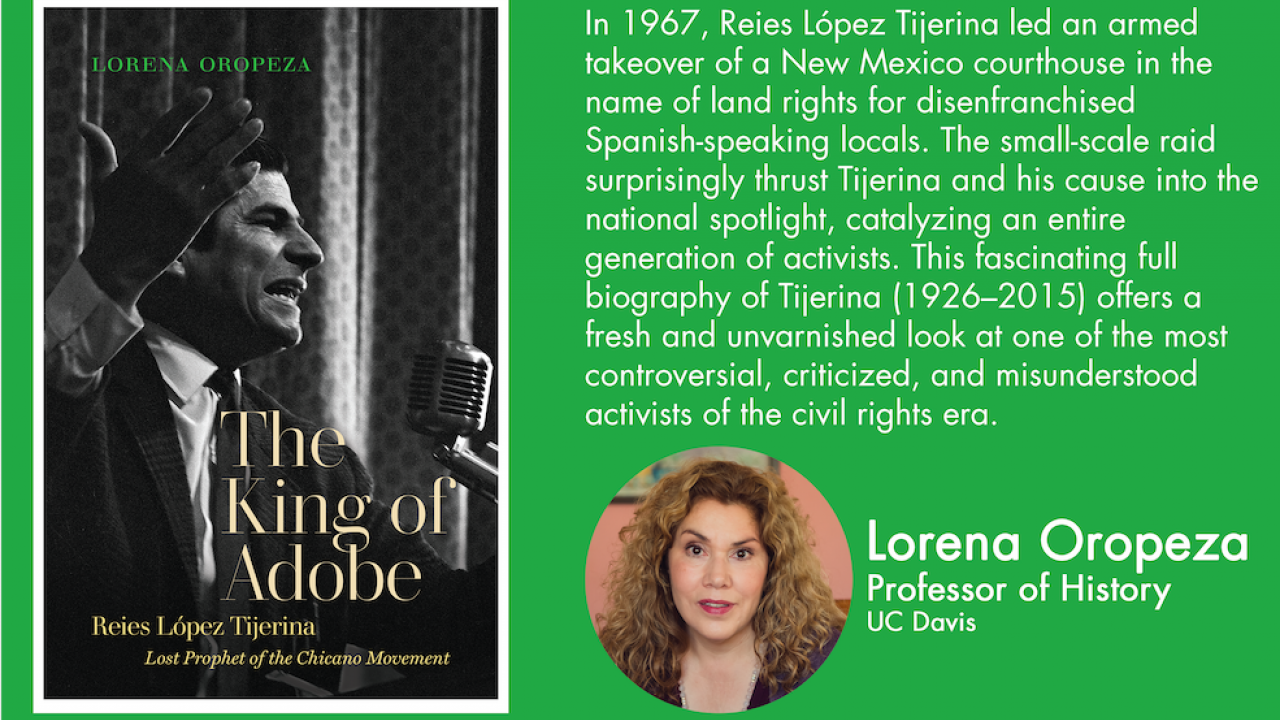

The Davis Humanities Institute celebrated the culmination of our 2020-2021 Faculty Book Chat series with a discussion of Dr. Lorena Oropeza’s The King of Adobe: Reies López Tijerina, Lost Prophet of the Chicano Movement (2020, The University of North Carolina Press). In conversation with DHI Director Jaimey Fisher, Oropeza read an excerpt from The King of Adobe, spoke about her process of researching Tijerina and writing the book, and answered questions from the audience. The King of Adobe, which won a 2020 Norris and Carol Hundley Award from the Pacific Coast Branch of the American Historical Association and was a 2020 Choice Outstanding Academic Title, is a full biography of Tijerina (1926-2015), who has been described as “one of the most controversial, criticized, and misunderstood activists of the civil rights era.”

In her remarks, Oropeza pointed out that most people only know of Tijerina from his leading role in the 1967 Courthouse Raid, which was a watershed moment in the land grant movement of the 60s and 70s. The land grant movement, in which Tijerina’s organization, La Alianza, was a key figure, fought to restore New Mexican land grants to the descendants of their Spanish colonial and Mexican owners. In the 1967 Courthouse Raid in Tierra Amarilla, New Mexico, Tijerina and others attempted to free fellow Alianzistas, who, unbeknownst to them, had already been released from Rio Arriba County Courthouse. Even as the Courthouse Raid made national headlines and catapulted Tijerina and La Alianza into the spotlight, it was also, as Oropeza argued, the beginning of the end of Tijerina’s influence.

In The King of Adobe, Oropeza focuses not only on the Courthouse Raid and Tijerina’s time with La Alianza, but also the lesser-known facets of Tijerina’s personality and political beliefs, facets that are crucial to understanding Tijerina as a complete and complex individual, but have mostly been left out of previous biographies and studies of Tijerina. Oropeza illustrated two of Tijerina’s lesser-known traits, his intense religiosity and his sexism, by sharing his recounting of a vision he had, which he called a “super dream,” in which he was specially called to be God’s secretary, while his wife obediently swept the floor of their home. The quiet, subservient role played by his wife mirrors the many sermons in which he preached about women being seen and not heard, serving their husbands, being valued for their premarital virginity and postmarital reproductivity, and being easily tempted by sexual urges.

Oropeza spoke of her experiences interviewing Tijerina and members of his family, including his first ex-wife and his daughter, who accused him of sexual assault. When Oropeza asked Tijerina about this accusation in an interview, he claimed that he was only “checking her virginity.” Yet Oropeza also experienced other disturbing elements of Tijerina’s personality first-hand: he repeatedly voiced antisemitic beliefs in their interviews, and at one point, at a dinner with his third wife and some of his daughters, he started yelling at Oropeza in front of everyone. Oropeza noted how his wife and daughters slowly left the room, leaving her alone to stand her ground against Tijerina’s rant.

At the same time that Tijerina preached sexist sermons and abused his family, Oropeza noted, Tijerina was also one of the few activists of color who reached out to make alliances with Black activists like Martin Luther King, Jr., as well as Indigenous activists. This was rare in a time in which many activists of color who were not Black or Indigenous were more invested in achieving their political aims by attempting to link themselves to whiteness, which often involved either ignoring or distancing themselves from Black and Indigenous movements. He also had a nuanced and powerful critique of the long history of American imperialism that was years ahead of its time and was critically important to his political allies in understanding and fighting against their own oppressions.

Oropeza ended her remarks by discussing the importance of studying all the elements of Tijerina’s personality, not just the ones that are most palatable or that fit the versions of history we like the best. She spoke of how he grappled with his own identity, at times seeing himself as a Mexican activist, at other times calling himself and his followers “Indohispano,” rejecting the term “Chicano” but also occasionally taking on the identity of a true-blue American patriot for strategic purposes. In a way, Oropeza argued, Tijerina’s complex personality and struggles with defining his identity mirrors the complexity of Chicanx/Latinx/Hispanic/Mexican identities and experiences in the borderlands, which occupy the unique position of being both Indigenous and settler, conqueror and conquered.

You can read reviews of and purchase The King of Adobe: Reies López Tijerina, Lost Prophet of the Chicano Movement here. Thank you for celebrating the culmination of our 2020-2021 Faculty Book Chats with Dr. Lorena Oropeza and the DHI. We look forward to seeing you in the fall for the beginning of our 2021-2022 season!