Exploring the History of American Disenfranchisement

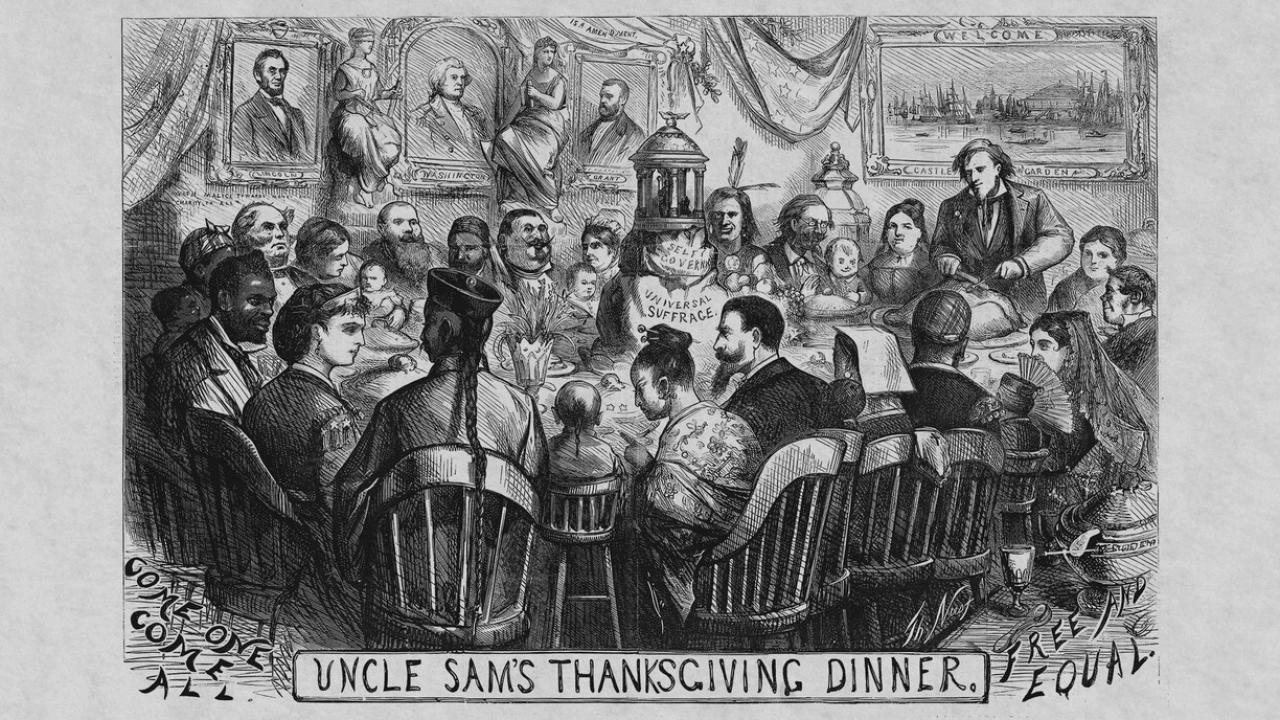

Disenfranchisement is an active American battleground. From states expanding vote-by-mail and Florida’s recent decision to enfranchise formerly imprisoned people, to Texas shutting down voting polls in districts with high populations of people of color and the rash of bills in state legislatures using the bogeyman of voter fraud to make voting more difficult, one thing is clear: fights about voter disenfranchisement are not going away any time soon.

What kind of future are we heading towards as American politicians and governments simultaneously fight for and against voter disenfranchisement? And what can we learn from the history of disenfranchisement in the United States?

Dr. Pippa Holloway’s research into 19th and early 20th century American disenfranchisement holds many answers to these questions. Holloway is the Douglas Southall Freeman Distinguished Professor of History at the University of Richmond. Her most recent monograph, Living In Infamy: Felon Disfranchisement and the History of American Citizenship, explores how racial discrimination, prison expansion, and the abandonment of the criminal reform and rehabilitation movement created a legal legacy that “continues to perpetuate a dichotomy of suffrage and citizenship that still affects our election outcomes today.”

In her talk at “Free People of Color: Race, Law and Freedom in the 19th and 20th Century,” a DHI Transcollege Cluster colloquium jointly sponsored by the Law School’s Aoki Center and the History Department, Holloway shared new research that developed from her work on Living in Infamy. Her talk, “Reconstruction and the Long History of Equal Access to Court Testimony,” explored other forms of disenfranchisement in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Felons in this era were not only stripped of their right to vote, but also disenfranchised of the ability to testify in court. In addition to mapping how court testimony was stolen from certain groups, Holloway’s talk also tracked the robust political movement that fought for testimony.

Holloway began her talk by pointing out that our present-day focus on citizen disenfranchisement as almost exclusively a matter of voting might make it difficult for us to understand why testifying in court was so important. Yet, as her research shows, during the 19th century testifying in court was often considered more important to one’s ability to function as a citizen than voting.

And it’s easy to see why.

In 19th century America, a felony was only one of the reasons for limitations on court testimony—other limitations also included race (in different regions of the country, people identified as Black, Native, Mexican, or Asian were prevented from testifying because of their race), religion (in California, for instance, Chinese immigrants could not testify because, it was argued, that they didn’t understand the sanctity of an oath because they weren’t Christian), age, and disability.

In her presentation, Holloway focused on racial limitations, and in particular, the issue of African Americans testifying in court in cases involving whites. As Holloway points out, many African Americans who were enslaved sought their own freedom through the court system. But the challenge of winning a freedom suit was even more difficult when the enslaved person couldn’t even testify in court as a witness to their own enslavement. Part of the reason these racist laws were upheld in the antebellum South is because they kept power in the hands of enslavers and made it difficult for African Americans to receive any redress from the courts. Holloway noted that in states that had an increasing number of free African Americans, laws keeping them from testifying in court were either amended or were interpreted so freely that they were effectively moot.

However, even Southern states took issue with the fact that their disenfranchisement of African American court testimony also limited the state’s own judicial and legal power. What was the court supposed to do when they were attempting to bring a case against a white person who had committed a crime and the only witness was African American? As Holloway put it, it became clear that “the courts wanted evidence and did not like these arbitrary and abstract prohibitions” that prevented them from obtaining evidence. From the state’s side, allowing court testimony from African Americans was necessary to try and convict criminals.

But, as Holloway pointed out, there was also a robust political movement that fought for the equalization of court testimony to protect the rights of African Americans. The ability to testify in court was pivotal in attempting to prosecute the violent crimes that whites often inflicted on African American communities. There were even those who claimed that freedom was dependent upon testifying in court, arguing that if an enslaved person could not testify in court in their own freedom suit, they would very likely be returned to slavery. As early as 1787, a law in Delaware proclaimed that free-born African Americans could not testify in court but could obtain redress—however, thanks in part to the rapidly growing population of free African Americans in Delaware, “redress” was interpreted widely to mean many different things, including testifying in court. Holloway also shared her research about a strangely-worded 1808 Maryland law that was reinterpreted to allow free-born African American testimony. The reinterpretation of this law became a precedent for many other cases. Holloway noted the high success of civil cases brought by African Americans against whites, especially in regards to the failure to repay debt.

As political and racial tension reached a fever pitch in the 1840s and 1850s, the debate about court testimony equalization became even more heated. One issue in the 1840 presidential election was whether the federal practice of equalizing testimony outweighed individual states’ rights to prevent court testimony. Later in the same decade, Illinois, Indiana, and Iowa all added racial exclusions to court testimony, while Delaware and Ohio weakened and critiqued racial barriers to testimony. In Indiana, the case of Woodward v. State questioned whether an African American could bring a case against the state. According to Holloway, the question was essentially if the state could be considered as a white person—and if so, could an African American bring a case against an entity understood to be white? (In the end, the ruling was that African Americans could in fact bring cases against the state.)

The Civil War left a lasting effect on the debate about equalizing court testimony. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 played an important role in equalizing testimony. But according to Holloway’s research, the real reason why Southern states changed their laws to allow African Americans to testify was because they did not want their cases removed to the Freedman’s Bureau. Southern states reluctantly equalized testimony so that they could avoid the Freedman’s Bureau, eventually abolishing the Bureau when they could and restoring power to local courts. White Southerners who had formerly fought against equalizing testimony argued that this new move supported the state’s right to hear all evidence, not the personal right of the witness. Or as Holloway stated, “this was not an expansion of African American rights but of court rights.” Further, these white Southerners believed that they could easily undermine the testimonies of African American witnesses so that even if they could testify, their testimony would not be seen as credible by white juries.

In the end, the equalization of court testimony was not about restoring rights to the disenfranchised; it was about affirming the primacy of the state and those in power.

This was nowhere clearer in the case of Blyew v. United States, in which the Supreme Court limited the scope of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 by agreeing with the state of Kentucky that they need not prosecute John Blyew, a white man, for the murder of Lucy Armstrong, an African American woman, because the only witnesses were her two African American children and an African American neighbor. In this ruling, the Supreme Court affirmed with what had been practiced in the courts of many slave states: that witnesses could be called when it served the court’s interests and requirement for justice. Holloway noted that this meant that it was up to state prosecutors (who, in the South, were overwhelmingly white and anti-Black), to decide whether to call a witness or not. The Civil Rights Act made it clear that prosecutors couldn’t bar testimony just because of the witness’s race, but in practice, prosecutors found many other ways to bar African American testimony.

If Blyew had been found differently, it would have allowed federal prosecutors to step in when state prosecutors refused to hear testimony. This could have in turn led to a court system that served victims of crime rather than the interests of the state. As Holloway reminded the audience, the ability to testify in court is not and has never been a right, and the refusal to call a key witness has been the deciding factor in many cases.

Holloway concluded her talk with a sobering statement: “we are not all equal in court today: limitations on [witness] competence become limitations on credibility, and we must think about threads between competence, credibility, race, and citizenship.” At the end she challenged the audience to ponder a series of questions: “What are the interests of justice? Whose interests does testifying in court serve? Who do courts serve?”

A lot has changed in America since the 19th century, but these questions still carry a great deal of weight.

You can view Dr. Holloway's lecture here