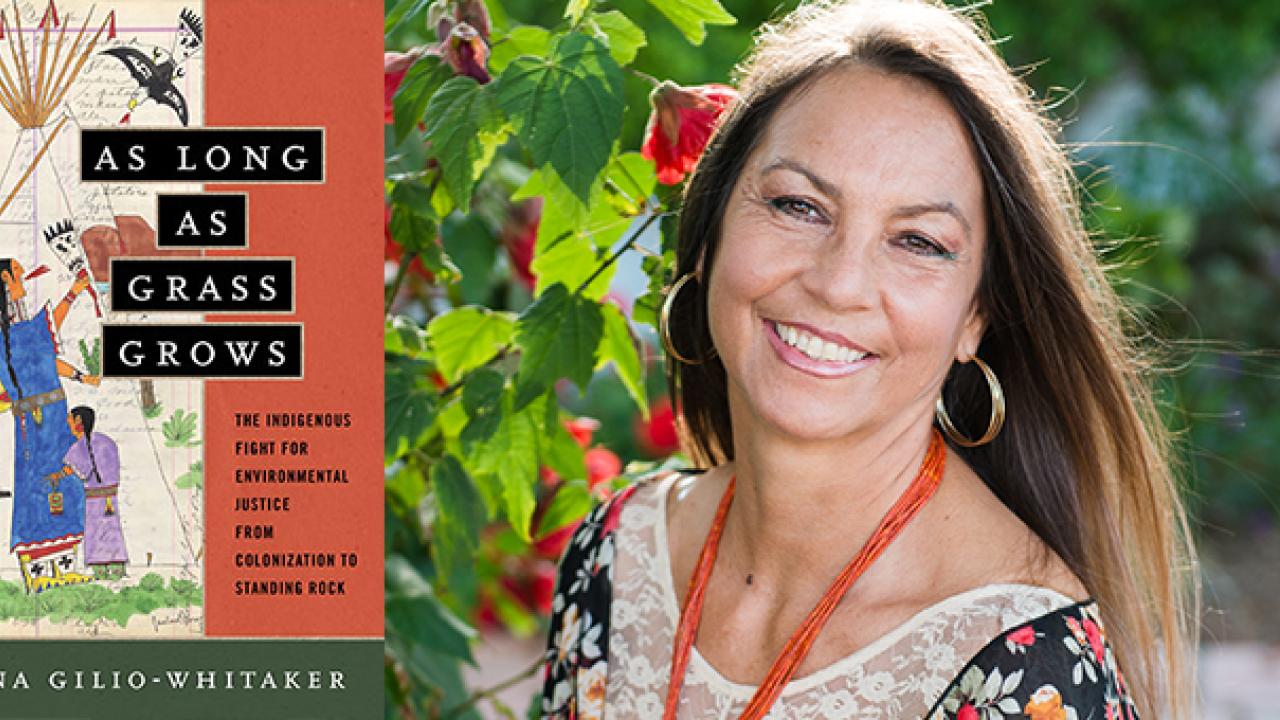

Dina Gilio-Whitaker and Indigenizing Environmental Justice

On January 9, 2020, author, educator, and speaker Dina Gilio-Whitaker (Colville Confederated Tribes) spoke in the Department of Native American Studies on her most recent book, As Long As Grass Grows: The Indigenous Fight for Environmental Justice from Colonization to Standing Rock (Beacon 2019). Her talk was titled “Environmental Justice in Indian Country.” Gilio-Whitaker’s research focuses on environmental justice and policy planning from an Indigenous feminist standpoint and uses broad, diverse, and collaborative methods. Her courses focus on topics ranging from traditional ecological knowledge, religion and philosophy, and Native Americans and surfing, to name a few. In addition to teaching American Indian Studies at California State University San Marcos, Gilio-Whitaker is the policy director and senior research associate at the Center for World Indigenous Studies. With Roxane Dunbar-Ortiz, she coauthored “All the Real Indians Died Off” - And 20 Other Myths About Native Americans (Beacon 2016).

In graduate school, Gilio-Whitaker noticed a serious lack of American Indians reflected in environmental justice scholarship. “The frameworks and histories that formulate that literature really don’t address the histories of colonialism in this country, and tribal sovereignty and nationhood,” Gilio-Whitaker explained. Noticing this prompted her to begin asking, “What does environmental justice look like through the lens of settler colonialism?”

Gilio-Whitaker defined environmental justice as several things: theory, activism, praxis, discourse, law, and policy. The movement emerged out of all of those things, especially in the United States South in the early 1980s. Initial issues in the movement were concerned with environmental inequalities that come with development, such as toxic development and unequal distributions of risk and harm in areas usually belonging to communities of color, such as Black and Latinx ones, particularly those that are low-income. Robert D. Bullard’s Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality is known as the key text of this era. However, Gilio-Whitaker argues, while environmental justice inculpates environmental racism for these violences, it does not account for settler colonialism. As such, its conventional definitions don’t work for Indigenous peoples.

For instance, she writes, environmental justice is “too narrow of a framework to contain our issues as a colonized people,” that is to say, as nations, not as ethnic minorities. She explains that a large oversight of the history of environmental justice is that it “collapses all ethnic minorities into one category” and “does not distinguish Native American nations/sovereignty” and their “different histories and relationship to land.” She used Standing Rock as a grounding example of “why environmental justice as it’s conventionally understood is not adequate”: the paradigm does not have the necessary tools to recognize treaty violations and sacred sites. For instance, “treaty rights on land outside reservation boundaries do not adequately protect sacred sites, and neither does the American Indian Religious Freedom Act.”

To ameliorate such oversights, Gilio-Whitaker argues, the field of environmental justice needs to be indigenized. This can happen by looking at it through the lens of settler colonialism and centering Indigenous experiences, which can in turn lead to different kinds of legal frameworks and conversations. Such perspectives require viewing settler colonialism as an ongoing structure, not just a historic event. It also necessitates understanding the role of white supremacy at the core of the environmental movement, and how that continues to play out in environmental injustices. Gilio-Whitaker’s scholarship adds a necessary history of the United States environmental movement from an Indigenous perspective.

Indigenized environmental justice, Gilio-Whitaker articulated, would perceive settler colonialism as environmental injustice, including but not limited to practices of genocide and slavery: both “outright killing and other policies of elimination” and “400 years of legalized Indian bondage,” read Gilio-Whitaker’s slide. It would account for environmental disruptions, or what Kyle Powys Whyte (2016) articulates as “the elimination of conditions of life necessary for collective continuance.” These conditions include systems of responsibility among humans and nonhumans, and disrupting them has been and continues to be integral to reimagined ideas of nature and wilderness that are and have been used to dispossess Native people of their land.

Gilio-Whitaker has implemented principles of indigenized environmental justice in Southern California coastal spaces. Indigenous feminist perspectives include the imperative to be a good relative. She brings “that ethic of relationality to surfing” in her work in the field of critical surf studies. She has worked with the California Coastal Commission on the precedent-setting Tribal Consultation Policy and Tribal Environmental Justice Policy. When California’s assembly passed bill 1782 to inaugurate surfing as the state sport, Gilio-Whitaker worked with lawmakers to include the state’s first official Indigenous land acknowledgement in the text of the document as well as the Indigenous place names of the famous surf locations celebrated in the bill. While Gilio-Whitaker is not alone in her approaches of coalition-building, “un-erasing” Indigenous peoples in their homelands, and working with decolonial feminist logics, she is at the forefront of the struggle.