Mellon Public Scholar Lizbeth De La Cruz Santana: Making Immigration Discourse More Inclusive through Art

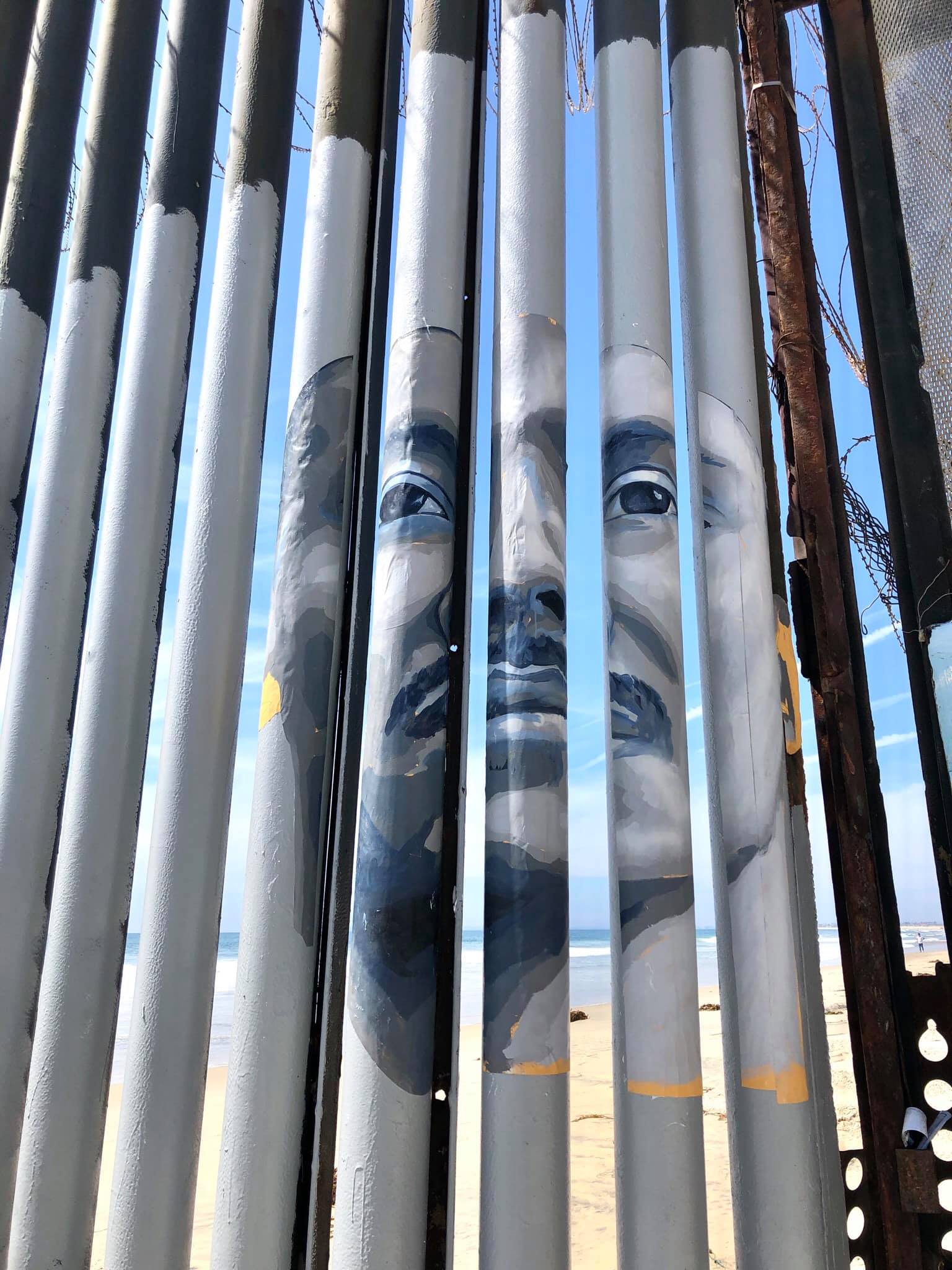

Lizbeth De La Cruz Santana, PhD candidate in Spanish at UC Davis, took her research on U.S./Mexico migration to the literal border this summer. As a 2019 Mellon Public Scholar, she conceived of, orchestrated, and painted her digitally interactive Playas de Tijuana Mural Project directly on the border wall.

The mural, which portrays seven faces that show what it means to be a childhood arrival to the United States from Mexico, builds on De La Cruz Santana’s previous archival work in UC Davis’ Humanizando la Deportación (Humanizing Deportation) working group and her own digital storytelling project, DACAmented: DREAMs Without Borders. Furthermore, it extends her dissertation inquiry, asking, “Who are the real childhood arrivals to the US?” In so doing, the mural works toward a more inclusive discussion of immigration to consider anyone who was brought into the United States as a child, regardless of immigration status.

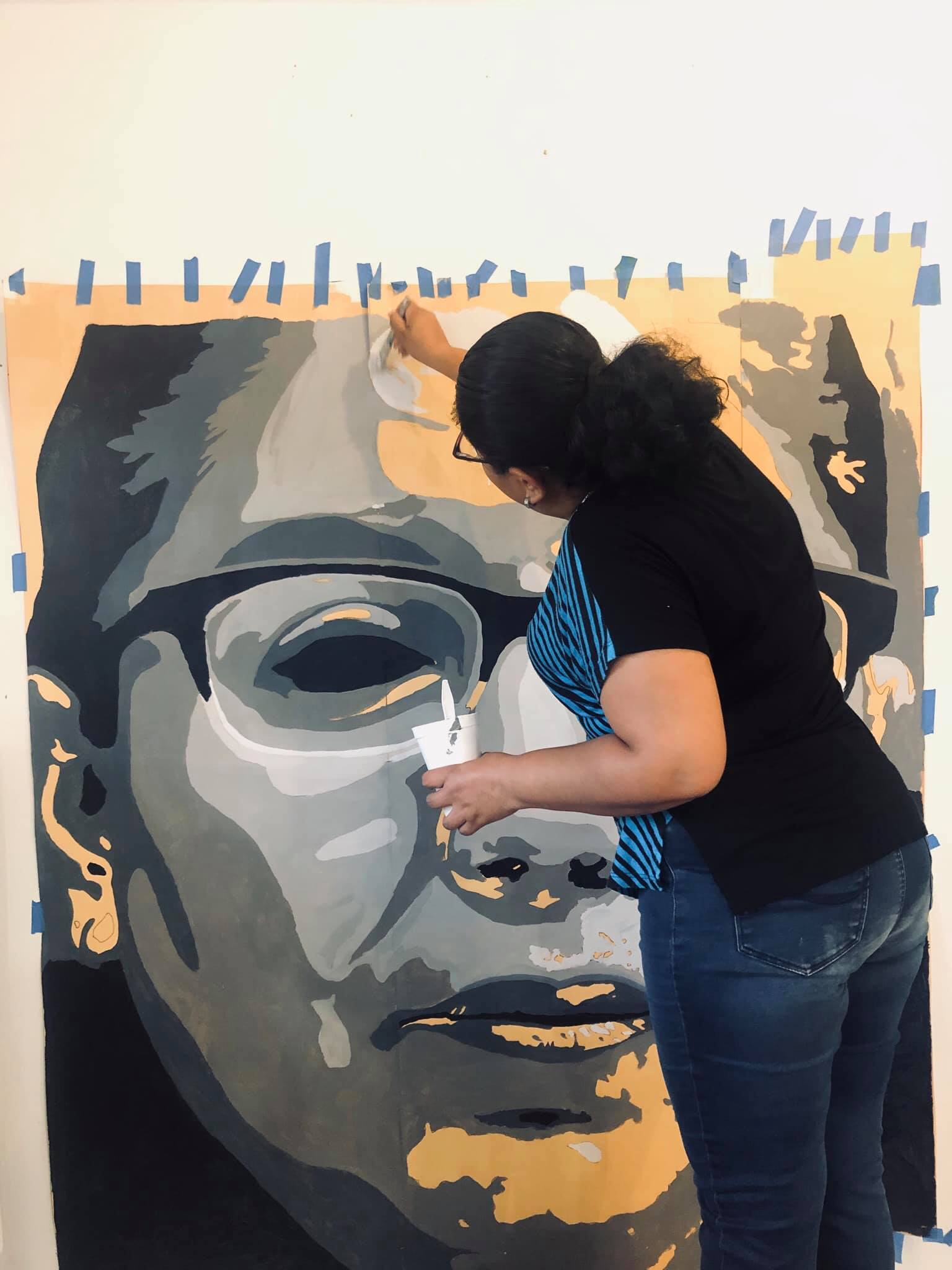

The mural idea came to De La Cruz Santana when she encountered murals painted on the border wall on a trip to Tijuana with Robert Irwin, Professor of Spanish at UC Davis, and the rest of the Humanizing Deportation working group in 2016. As a Mellon Public Scholar, she was supported in carrying out a publicly-engaged research project this summer, and with the guidance of advisor Maceo Montoya, Associate Professor of Chicana/o Studies at UC Davis, De La Cruz Santana decided to use her artistic skills to investigate what it means to be a childhood arrival who has been deported in interactive, collaborative border mural form on the Mexico side of the border. “As an academic,” De La Cruz Santana noted, “I have access to stories because of research that regular people don’t have.”

The mural consists of seven portraits of childhood arrivals to the U.S., and “for me,” De La Cruz Santana explained, “the most rewarding part was that the participants themselves all participated in painting part of or most of their own portraits.” She chose to paint on the Mexico side of the border not only because it is illegal to paint on the United States side, but also because it is crucial that Mexico pays attention to what happens when people are deported.

While De La Cruz Santana was solely responsible for the orchestration of the mural, a multitude of people were involved in its production. Among them were lead artist Mauro Carrera, a Fresno-based artist and teacher who suggested using wheatpaste as a method to make a mural on the difficult-to-paint fragmented steel border wall. Muralist Enrique Chiu acted as a local liaison and took De La Cruz Santana to paint with him at the beach at their first meeting.

Considering questions of who the mural belongs to is integral to De La Cruz Santana’s project of inclusivity in border studies. The community project complicates the question of ownership that so many hegemonic narratives presume, and the engaged public scholarship of the cultural project adds a rich dimension to her dissertation. Throughout the Playas de Tijuana Mural Project, De La Cruz Santana consistently had to evaluate the risks and questions of the work. After all, she pointed out, “there are no check-ins after return from the field,” and the work wasn’t physically, emotionally, or mentally easy. Holding a strong sense of community and ethics has kept the project and its participants strong and forward-looking.

The digital component was crucial to the project, and marked the first time an artist has incorporated Quick Response (QR) codes into a border wall project. Even when faced with time limitations and logistical complexities, De la Cruz Santana was committed to the idea. She sent her QR code sheet to be printed, and upon receiving the codes, immediately cut them up and started pasting them herself. Reporters and the public responded enthusiastically to the digital aspect of the project. The QR codes enable people who can’t go to Tijuana themselves—whether for legal, financial, or other reasons—to interact with the mural as well.

As a first-generation woman of color carrying out a complex project in a field new to her, De La Cruz Santana faced a whole host of challenges. However, conceptualizing, planning, and executing the Playas de Tijuana Mural Project has proven that she can pull off any project she deems needed and ethical. Giving back to the people that helped her paint is imperative, and she is currently planning two initiatives that people interested in helping out are warmly invited to get involved with.

The DREAM Will binational support group network for childhood arrivals, which developed out of the mural, is a supporting a reunification campaign for the Estrada family. Karla Estrada is one of the mural subjects. The campaign is gathering resources to reunify the binational family geographically despite the physical barrier of the border fence in Friendship Park in Tijuana in January of 2020. Along with future lawyer and current Al Otro Lado intern Danilo Castilo, De La Cruz Santana is creating a guide for migrants to find resources, shelter, health services, computer resources, and other necessary services in Tijuana. The project, Migri-Pocket Guide, will take both paper and app forms accessible to multilingual communities of literate and illiterate populations.

If you or someone you know are interested in getting involved in either of these projects, collaborations and sponsorships are welcome; interested parties should contact De La Cruz Santana directly. De La Cruz Santana put it best: “It’s only fair that we give back to each of [the muralists], depending on what they need.”