Mellon Public Scholar Rebecca Hogue: Protecting Mauna Kea as Pacific Environmental Justice Action

This summer, Ph.D. candidate Rebecca Hogue confronted the political stakes and commitments of her research on Pacific Islander climate change activism by joining in the Mauna Kea protection movement. As a 2019 Mellon Public Scholar, Hogue was supported in thinking through what it can mean to show up and step back as a settler ally and was given the “chance to embody being an accomplice or co-conspirator.”

Hogue came to her research on environmental justice discourse within the Pacific Island diaspora in Northern California via growing up in Hawai‘i as a fourth-generation settler feeling “the long impact of settler colonialism.” Although she did not have the language of settler colonialism as a child, she was deeply moved by the one hundred-year anniversary of the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy and aware of “the great disparities of health and wealth” between indigenous Hawaiians and settlers. Hogue studied in American Studies and her master’s thesis examined representations of land from multicultural approaches in Hawai‘i and addressed questions around land, displacement, erasure, environmental justice, and environmental racism.

As a Ph.D. candidate in English with a designated emphasis in Native American Studies at UC Davis, Hogue found that “discourses around indigeneity were the tools I needed to discuss these issues in the Pacific” and has studied with her Mellon Public Scholars mentor Prof. Beth Rose Middleton as well as with Prof. Inés Hernández-Avila in the Department of Native American Studies. Hogue is currently completing her dissertation as a 2019-20 Mellon/ACLS Dissertation Completion Fellow.

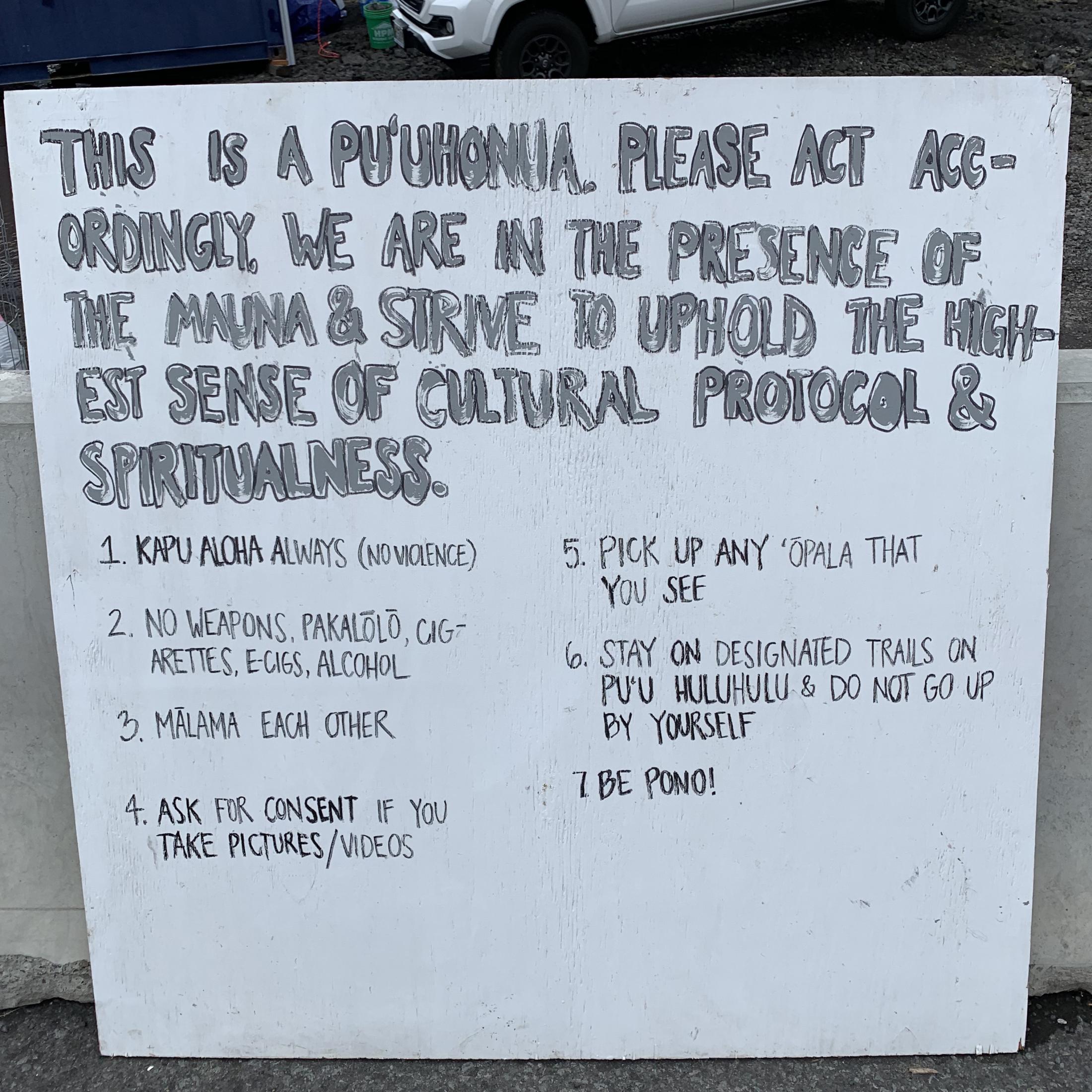

As a Mellon Public Scholar, Hogue “thought [she] was going to be producing a thing — instead, [she] went and had an embodied experience.” Hogue came to her work on environmental justice discourse among the Pacific Island diaspora in Northern California through interpersonal relationships. In these relationships, Hogue emphasizes how she can be of service and practices personal interrogation and reflection as a method. When asked about her methods, Hogue discussed the qualities of generosity and sharing that pervade the Mauna, which are all part of the philosophy of “kapu aloha.” “I knew,” she explained, “that the first thing I would do, and did in advance, was to give in a variety of ways that I was capable of [and that people on the Mauna] had asked for.” This meant donating to the bail fund, donating airline miles for people called to the Mauna to get there, and purchasing and bringing objects such as headlamps and batteries to the movement.

Hogue emphasized the necessity of listening in order “to work in a way that is of use to those who are leading the movement” and “be of use in whatever utilitarian capacity needed.” She spoke to the incredible sensory experience of arriving at Pu’uhonua o Pu’uhuluhulu and listening and watching in order to get oriented and see where she could contribute. When a hurricane passed just to the southeast of the Big Island, Hogue helped people set up tents, served and delivered food, and helped the kitchen line trays with tinfoil. Although an infrastructure—including a kitchen, accommodations, storage, and ceremony—sprang up quickly at Pu’uhonua o Pu’uhuluhulu, the “evolving nature of the camp leads to responsibilities falling largely on people who are in it for the long haul.” Hogue wanted to lighten the load to the extent that she could.

Hogue finds it her responsibility, as a settler who grew up in the incredible place of Hawai’i, “to be invested and be involved.” Moreover, she sees it as a privilege “to be in the position that I am—in affiliation with the University—and to be someone on the Continent who shares information about what’s happening in the Pacific.” Her Mellon Public Scholarship will affect many aspects of her future teaching, such as how she will discuss sovereignty actions with her students, encourage them to do decolonizing work, and not only promote but to champion and to “think through indigenous epistemologies in... reading practices.”

Hogue maintains that it is “our responsibility as settlers to educate ourselves about the land in which we are privileged to live” and, like the work of Vicente M. Diaz, connects this responsibility to the geographic specificity of traditional ecological knowledge which cannot be extracted and generalized. Being invited to attend ceremony three times daily, practice hula, sing mele, and practice ‘Ōlelo are integral to the place the protectors are protecting. This gets at something that is at the heart of Hogue’s work in general: “there are so many of these components that are expressed through indigenous epistemologies that have these beautiful and really powerful relational methods” that she “honor[s] to the extent [she] is capable” and of which she intends to “learn as much as [she] possibly can.